The Sun King in the Marais

The Sun King in the Marais

.jpg) The Marais, the most stylish neighborhood in 17th century Paris, would never be the same after the reign of Louis XIV. The Sun King, who did so much to make France the power in Europe, inadvertently cast a shadow on the Marais.

The Marais, the most stylish neighborhood in 17th century Paris, would never be the same after the reign of Louis XIV. The Sun King, who did so much to make France the power in Europe, inadvertently cast a shadow on the Marais.

Louis’s reign was defined by prestige, glamour and glory. In deciding to move to Versailles, he shifted the center of power southwest, about 30 kilometers from Paris, to his magnificent palace, showcasing splendid gardens and fountains, a stunning hall of mirrors, but above all, his absolute power. Versailles became the hub of refinement. And the king was at its center.

As time went on, Parisian high-society began to flock to the Left Bank, an easier commute to Versailles. This was toward the end of the 17th century, after the king officially moved his court in 1682. And so the elegant quarter of the 18th century sprang up around the grand and incongruent church of St. Sulpice and its surroundings and the Marais went into decline.

.jpg)

.jpg)

However, the Marais remained a nucleus of culture during the 17th century. Aristocrats attended salons to banter and parry their wit. An ambitious host or hostess would open their townhouse to the smart set. Amusement was the aim, along with refining tastes and gaining knowledge through clever conversation and readings. Unexpectedly, however, the Marais and the salon soon became the breeding ground for one of the king’s most notorious vices: his mistresses.

Two of Louis’s long-term mistresses, Athénaïs de Montespan and Françoise Scarron, later Mme de Maintenon, would meet at the Hôtel d’Albret (31, rue des Francs Bourgeois). This elegant townhouse still stands. The sinuous street, rue Franc Bourgeois, lined with one mansion after another, was the Park Avenue of its day. And it is no surprise that the Hôtel d’Albret was one of the finest gathering places for the well-heeled. Athénaïs was a regular when she was already Louis’s mistress. Françoise, a bit down-on-her-luck, was also gravitating to this world.

For a royal, marriage in the 17th century was rarely an affair of the heart. The arrangement usually came with some political alliance. When Louis was married to the Infanta of Spain (Maria-Thérèse) in 1660, peace between the two great powers was assured. However, it was said that Louis blanched at the sight of his new bride. No great beauty, she was Louis’s first cousin and looked slightly inbred. The Infanta was dumpy, had stubby black teeth and stumpy legs. She always spoke French with a thick Spanish accent, and worst of all, she lacked wit! The king made do, and always treated her respectfully. After the King had provided an heir to the throne, his attentions began to wander...

Louis’s first serious affair of the heart was Louise de la Vallière. His mother, Anne of Austria, engineered the meeting. Anne, concerned that Louis was showing interest in Henriette, the wife of Louis’s flamboyant homosexual brother, came up with a distraction. She had several attractive single women fluttering around Louis during meals. Her ploy worked. Louis became smitten with the lovely Louise.

As a young adult, the Sun King was somewhat shy. The sweet, unsophisticated Louise was his first initiation into love and historians cast this bond as an idyllic affair. However, the callow Louise always felt uncomfortable in her role as the titular mistress. Everyone’s favorite 17th century gossip, the Marquise de Sévigné, dubbed Louise “a shrinking violet.” Perhaps Louise’s greatest error was to choose as friend and confidante (someone to shield herself from the back-biting court), the sultry Athénaïs de Montespan.

Françoise Athénaïs de Mortemart, Madame de Montespan, was a tempestuous creature. An exquisitely beautiful woman, one courtier called her “the rare masterpiece of the gods.” Voluptuous, clever and charming, she had sex appeal. And the king noticed.

.jpg)

Athénaïs held the king’s attentions for an incredible 12 years, having seven illegitimate children thanks to his ardent affections. This was precisely the problem. Athénaïs was already married, so the children needed to be brought up with prudence and in secrecy.

Mme de Montespan’s choice of governess was clear from the outset. She wanted someone who would pose no threat in terms of Louis’s affections as she herself had with Louise. She immediately thought of her friend, the Widow Scarron, her chum from the Albret home.

In an ironic twist, however, each of Louis’s long-term mistresses would be provided unwittingly by the previous one. This is precisely what happened with Widow Scarron.

A bright, extremely Catholic and reserved woman, Françoise d’Aubigny was attractive, but not alluring like Athénaïs. At first, the King was not fond of her, but he soon grew to appreciate her kindness to his children and her discretion.

Hers was an incredible destiny filled with reversals. Born in a debtor’s prison, Françoise d’Aubigny came from a noble, but penniless family. She lost her parents early on. Without a proper dowry, the nunnery seemed her only option. However the bawdy wit Paul Scarron, a twisted invalid in a new-fangled wheelchair, offered her marriage. He held court at his salon in the Marais (his mansion no longer exists), and it was there Françoise met great artists and intellects of the day. She mingled with the upper crust and learned to make herself indispensable to them.

This was a wise move on her part, because when Scarron died, he left her nothing but debts. The wealthy came to her aid and she was given a small allowance by the King’s mother, Anne of Austria. During this period she spent a lot of time at the Albret home and met Athénaïs. She would eventually receive the job offer of a lifetime: secret governess to the king’s “royal bastards.”

Bringing these children up in the utmost secrecy was not an easy task, but the Widow Scarron fulfilled her role. In time, the king legitimized the children and moved them to apartments at Versailles along with Françoise, on whom he bestowed the title: Madame de Maintenon.

Perhaps she was a woman with a mission. As a pious Catholic, Madame de Maintenon wanted to save the king’s soul. This was no easy feat. Even the King’s confessor, Père la Chaise, the priest associated with the Baroque church St. Paul in the Marais (rue St. Antoine) had to take his leave when he saw a situation looming that would be tricky to absolve.

And in retrospect, even while the king was head-over-heels in love with Athénaïs, he had countless passing fancies: Madame de Ludre, Mademoiselle des Oeillets, Mme de Thiange (Athénaïs’s sister), the Princess Soubise (eventually she built the largest mansion in the Marais thanks to her liaison with the king), and Mademoiselle de Fontange are the most notable.

Clearly, the king had powerful lusts when it came to food, sex and building. His appetites could hardly be quelled and polygamy seemed to be the rule. At one point, his mother criticized him for his philandering, saying he was a poor role model. The king actually broke down, but claimed he couldn’t help himself.

Later he began to lose interest in Athénaïs. Her weight gain was one of the causes. The King also grew tired of her explosive fits. And her implication in the Affair of the Poisons was probably the fatal blow.

Wags at court had a field day as it became obvious the king was infatuated with Madame de Maintenon. They would say the king was with the “has-been” and the “now” (the name “Maintenon” is a homonym for the word “maintenant” meaning “now” in French).

Eventually Athénaïs had no choice but to retire from court. And when the Queen, Marie-Therese, died in 1683, everyone wondered who the most powerful man in Europe would wed? What Royal would have him? It turned out to be Madame de Maintenon. They married in a secret ceremony. Louis was faithful to her in the end. So much so, that Françoise complained of having to perform her marital duties into her 70s. Yet the king’s devotion to her was touching and he called her “my solidity.”

And so the extraordinary story of the Sun King, his many loves, the Marais and Versailles comes to a close.

Poison and Passion in the Marais

The year : 1676.

The place : the Marais.

Hub of the aristocracy and the elegant stomping grounds for the upper crust, the Marais was the place to live for everybody who was anybody! And one of its very own residents, a high-society lady, the Marquise de Brinvilliers, was discovered to have been poisoning her family. Who would have thought? Not her brothers or her father. They were the first to be expedited by her powders.

Hub of the aristocracy and the elegant stomping grounds for the upper crust, the Marais was the place to live for everybody who was anybody! And one of its very own residents, a high-society lady, the Marquise de Brinvilliers, was discovered to have been poisoning her family. Who would have thought? Not her brothers or her father. They were the first to be expedited by her powders.When the news broke, people were stunned. The word spread like wildfire since it was sensational news of the day -- almost tantamount to a modern-day O.J. Simpson media event.

Many believed Brinvilliers practiced how to effectively use poison when she had volunteered at the Hôtel Dieu (literally God’s Hospital -- Paris’ oldest hospital dating from the 7th century still stands, albeit rebuilt in the 19th century).

It was said she administered her poisons to observe the effects on the unfortunate patients. With an average of three to a bed, and not a fabulous recovery rate, certainly nobody would have noticed anyway. Athough there is no evidence of Brinvilliers doing such things, people still thought her guilty.

The origins of Brinvilliers’s crimes can be traced to her father, the Marquis de Brinvilliers, marrying her off to a man she didn't particularly love. So naturally she began to have an affair – not a stunning deviation from the norm in France.

When St. Croix was released from prison, he and Brinvilliers resumed their affair and, using his newfound knowledge, they set to work poisoning her family. Her father was first to go. Brinvilliers claimed when she was eventually brought to trial that ‘he deserved it’. Then it was her brothers’ turn. She hoped to inherit their money. Her husband was next in line. However, Godon de St.Croix, concerned he might be stuck with Brinvilliers, visited the husband and gave him an antidote. The history books record that the husband survived, but with a seriously damaged digestive tract.

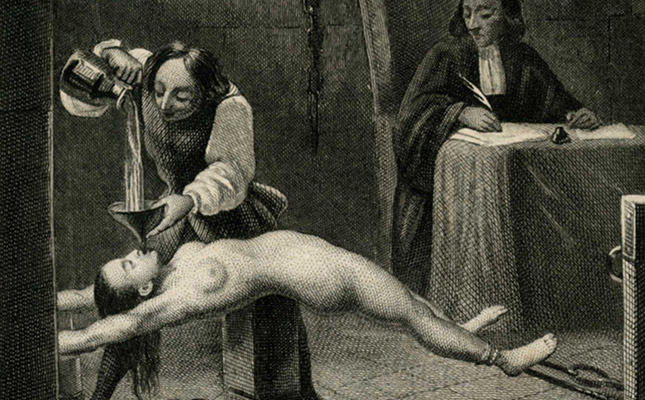

Then Godon de St. Croix died... supposedly of natural causes. Brinvilliers inadvertently brought attention to herself when she persistently tried to obtain a casket taken into police custody that was filled with compromising letters and recipes describing the poisons and their effects. Brinvilliers had no other choice but to flee – first to England, then Belgium. After great effort on the part of the first Police Lieutenant of Paris, la Reynie, she was brought back to Paris. Justice had to be rendered, so she was tried (or, more accurately, tortured at the Conciergerie).

The Marquise de Sévigné (one of the Marais’ most elegant ladies, famous for her witty letters) attended the execution, renting a window in a house on the bridge Notre Dame. The execution was one of the most highly attended in France. Sévigné’s now-famous quip was recorded for posterity. She wrote to her daughter, “Well, it’s all over and done with. Brinvilliers is in the air. Her poor little body was thrown after the execution into a very big fire, and the ashes to the winds, so that we shall breathe her, and through the communication of the subtle spirits, we shall develop some poisoning urge which will astonish us all..."

The Marquise de Sévigné (one of the Marais’ most elegant ladies, famous for her witty letters) attended the execution, renting a window in a house on the bridge Notre Dame. The execution was one of the most highly attended in France. Sévigné’s now-famous quip was recorded for posterity. She wrote to her daughter, “Well, it’s all over and done with. Brinvilliers is in the air. Her poor little body was thrown after the execution into a very big fire, and the ashes to the winds, so that we shall breathe her, and through the communication of the subtle spirits, we shall develop some poisoning urge which will astonish us all..."

.jpg)